On the Inauthenticity of Hip-Hop, Tekashi 69 and the Impact on Youth

(Originally published by Dr. Edmund Adjapong on Medium)

I was not surprised when the news broke that Brooklyn rapper Tekashi69 was cooperating with federal prosecutors and reportedly pleading guilty to charges arising from his involvement with the Nine Trey Bloods gang. Since Tekashi received mainstream attention, I was always troubled by his portrayal of hip-hop culture. Tekashi’s career launched with the instant success of his first hit song “Gummo,” which glorifies gang culture, violence, and misogyny. The music video for “Gummo,” which was released in October of 2017, shared images of dozens of Black men pointing guns at the camera, dancing and flaunting red bandanas paying homage to the Bloods gang.

Tekashi became affiliated with the Nine Trey Bloods gang in September of 2017, just a month before his hit song “Gummo” was released. Many believe that Takashi aligned himself with his former manager Kifano “Shotti” Jordan, who is a known member of the Nine Trey Bloods gang, and sought gang affiliation to increase his credibility as a hip-hop artist. Reportedly, before ever meeting Shotti, Tekashi was never involved in a gang.

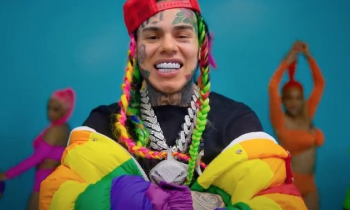

Known for his signature face tattoos and rainbow-colored hair, Tekashi created a successful viral internet personality through Instagram where he garnered over 15 million followers and is well known for his over the top antics. He constructed a narrative around himself as a self-indulged villain in hip-hop who attracted drama and gun violence almost everywhere he went. During his career, Tekashi has had public feuds with Hot 97 Radio Personality Ebro Darden, Rappers Cheif Keef, The Game, Trippie Red and YG to name a few. The controversy surrounding Tekashi only helped his career, as 10 of his songs reached the Billboard 100 charts in his first year as an artist.

Tekashi’s recent arrest is not his first time coming in contact with the criminal justice system. He was arrested three times in 2018. When federal agents executed a search warrant of Tekashi’s home, they found an illegal assault rifle. Federal agents also found a book bag that was stolen during an armed robbery that involved Tekashi and was reportedly executed by the Nine Trey Bloods. A few weeks before his November arrest, Tekashi took to Instagram to tell his fans that he fired his whole team, including his manager Shotti. This was Tekashi’s attempt to disaffiliate from the Nine Trey Bloods gang, but it would prove to be too late.

Tekashi69 was arrested in November for charges that stem from a RICO (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations) investigation that include a number of crimes: armed robbery, conspiracy to commit murder, and drug distribution. Tekashi69 faces a mandatory minimum sentence of 47 years in federal prison if convicted.

Tekashi’s decision to construct a narrative around himself as a villain who publicly welcomed and celebrated violence is an example of the problem of inauthenticity in hip-hop culture. Tekashi’s decisions to both join and disaffiliate from the gang and its members in rash moments reveal his true intention in participating in gang culture. Tekashi is no real gangster. Rather he is using gang culture ingeniously as a means to achieve personal gain. Hip-hop at its core values community, not individuals who want to mainly capitalize off of the culture. This narrative particularly has had adverse effects on Tekashi ’s life and career, but it also one that is harmful hip-hop culture and the hip-hop generation of his time. If the reports are accurate, one can argue that Takashi’s affiliation with the Nine Trey Bloods and former manager Shotti helped propel his music career and gave him credibility as an untouchable villain in hip-hop. Additionally, his association with the Nine Trey Bloods gave him an allowance in the streets to create disputes with anyone because he could always depend on the protection of his gang and loyal fanbase. Is it possible that Tekashi 69 portrayed an inauthentic, arrogant persona as a means to a successful rap career? Once Tekashi realized his gangster persona had real consequences, he tried to disaffiliate. But it was too late.

America loves the image a hip-hop artist toting guns, glorifying violence and inciting beef regularly. They love to see a hip-hop artist that magnifies negative stereotypes of the hip-hop generation — this image of hip-hop feed directly into White America’s racially biased perception of urban and hip-hop youth. White Americans, the largest consumer group of hip-hop, who participate in hip-hop culture solely through consuming hip-hop music, have a limited understanding of what hip-hop culture indeed is. Rather than doing the necessary work to learn more about a culture that is not original to them, they use their limited understandings of hip-hop culture to make sense of the realities of Black Americans and participants of the hip-hop generation. Tekashi’s persona and other personas like his are not accurate depictions of what hip-hop is or what it was intended to be. The question of whether Tekashi’s persona is authentic or not is up for debate, but its effects on the culture of hip-hop are not. Because Hip-hop is a medium where people from historically marginalized communities and groups can share stories of their realities and is one that is inclusive of the identities of millions of its followers across the globe, it is not fair for consumer based hip-hop to emphasize a narrow narrative of what hip-hop is. It is not solely what Tekashi and artist like him portray. We must consider the effects of this one-dimensional narrative on participants’ and consumers’ perceptions of hip-hop culture and Blackness.

Consequently, young people who may not have yet gained the skills to be critical of media and its messaging may fall victim to believing that they can engage in similar activities as Tekashi, without a clear understanding the consequences. Young people from across the nation and world think that Tekashi is an exemplar of hip-hop culture because his stereotypical narrative feeds into false narratives that have existed about communities of color for decades. Further, it is possible that youth who aspire to be successful artist in hip-hop can fall victim to the problematic narratives peddled by their favorite artist every day, like Tekashi, and may believe that they must emulate their idols and affiliate with a violent lifestyle to launch their music career or bring them success on a social media platforms.

Ultimately, I am empathetic to Tekashi and his current situation. In my experience with working with youth who come from marginalized communities, I understand that Tekashi at one point was a teenager seeking acceptance and comradery that he didn’t receive in his school and ended up finding it and gaining it elsewhere. The irony of Tekashi 69 is that on his search to be the king of New York, he became a scapegoat of the new generation of hip-hop.

Dr. Edmund Adjapong is an assistant professor in the Education Studies Department at Seton Hall University.

This post was written by am